When turning and standing in between trips, buses can create traffic jams.Bus terminal facilities are frequently located on valuable land.Buses turning around waste time. For a portion of their journeys, passengers who want to get across the city center will need to walk or change buses. Routes that end in city centers have the following benefits: Congestion is less likely to interfere with schedules. At a common terminus, there may be a convenient transfer between routes.

COMMUTER ACCESS

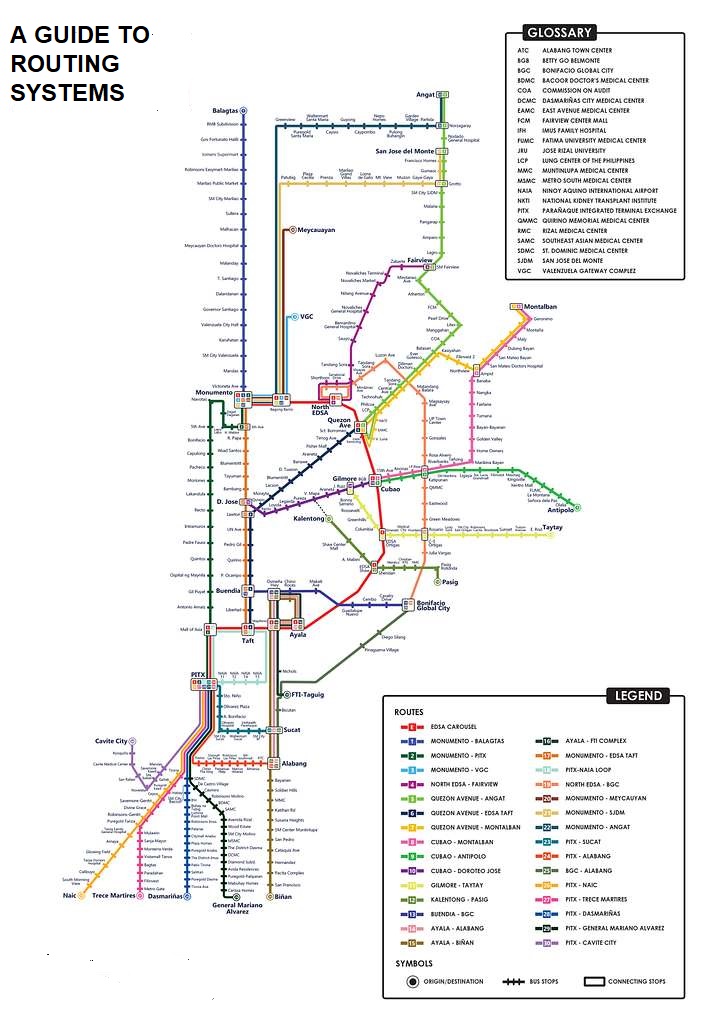

In some situations, a hub-and-spoke transportation bus schedule for bus system could be suitable, especially in smaller towns. This feature implies that all routes converge at a single hub, and that travelers can switch between routes to get to any two locations within the city. Such a bus service system might be appropriate in situations with short travel periods and high service frequency to reduce transfer times.

However, in general, a large percentage of indirect travel is unacceptable, especially for regular commuter traffic and in areas where traffic congestion is an issue. The bus routes themselves could be different. The end-to-end route is the most basic and widely used kind of route. It runs between two locations and uses the same roads in both directions, with the exception of one-way

A route that alternates between circular and straight sections provides an additional choice. The bus travels in a loop at the end of the journey rather than turning and going back the inward way. After finishing the loop, it returns to the inward path, pausing in the middle region for as little time as necessary to drop off and pick up passengers.

Instead of operating throughout the city core, a central business district may find that such an arrangement works very well. Because passengers can board and disembark from the bus at any point within the circuit, it may offer greater service coverage than a terminal operation.

SIMPLE TURNAROUND INFRASTRUCTURE

There is less complexity in fare arrangements. Although each situation must be evaluated on its own merits, generally speaking, the benefits of running routes through the city center exceed the drawbacks. There are several methods for managing non-radial passenger travels. Operating many routes connecting different suburbs without reaching the city center—possibly including circular routes connecting distant points—is frequently acceptable in large cities. These are frequently driven by smaller cars than those seen on routes that go to the city center. The main radial routes can occasionally be extended or diverted to accommodate inter-suburban transportation.

Several feeder bus routes may be part of a transportation bus schedule for bus network, feeding passengers to rail lines and trunk bus routes. These provide an alternative to running numerous routes that branch off to serve locations off the main route along a shared corridor. When there is enough demand from the outlying places to warrant it, through bus services should typically be run; however, in situations when demand is minimal, feeder services with smaller vehicles are frequently more cost-effective.

Additionally, it is typically preferred to employ small cars on a route when road conditions prohibit the use of larger vehicles, feeding into a service that uses larger buses for the main segment. As a result, tiny buses no longer need to travel on major city routes alongside larger buses.

SUMMARY

Forks near one or both ends to service various terminal points are another variation of the straight route. Despite sharing most of their length, these are occasionally considered distinct routes. Some routes could have a loop at each end and resemble dumbbells. These are typically encountered where buses travel from one suburb to another across the city center, circling the outermost residential districts.

Routes of some or all of these kinds may be found in a route network. Bus routes do not breach the arbitrary barriers that plague certain networks. For instance, in Beijing, inner and outer bus lines converge at a number of locations on the outside of the city center. It is necessary for passengers to switch between vehicles. Similar circumstances arise at municipal borders in Indonesia as a result of the way public transportation services are governed.

Even though convenient interchanges are frequently offered, customers’ travel times are prolonged by the necessity to switch bus schedule for bus vehicles, and the longer turnaround times result in less use of vehicles.